You may be familiar with “self-determination” in the context of foundational government documents and speeches from people long-dead.

Traditionally, self-determination has been more used in this diplomatic and political context to describe the process a country undergoes to assert its independence.

However, self-determination also has a more personal and psychology-relevant meaning today: the ability or process of making one’s own choices and controlling one’s own life.

Self-determination is a vital piece of psychological wellbeing; as you may expect, people like to feel control of their own lives.

In addition to this idea of controlling one’s own destiny, the theory of self-determination is relevant to anyone hoping to guide their live more.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

Self-Determination Theory, or SDT, links personality, human motivation, and optimal functioning. It posits that there are two main types of motivation—intrinsic and extrinsic—and that both are powerful forces in shaping who we are and how we behave (Deci & Ryan, 2008).

It is a theory that grew out of researchers Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan’s work on motivation in the 1970s and 1980s. Although it has grown and expanded since then, the basic tenets of the theory come from Deci and Ryan’s seminal 1985 book on the topic.

According to Deci and Ryan, extrinsic motivation is a drive to behave in certain ways based on external sources and it results in external rewards (1985). Such sources include grading systems, employee evaluations, awards and accolades, and the respect and admiration of others.

On the other hand, intrinsic motivation comes from within. There are internal drives that inspire us to behave in certain ways, including our core values, our interests, and our personal sense of morality.

It might seem like intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation are diametrically opposed—with intrinsic driving behavior in keeping with our “ideal self” and extrinsic leading us to conform with the standards of others—but there is another important distinction in the types of motivation. SDT differentiates between autonomous motivation and controlled motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2008).

Autonomous motivation includes motivation that comes from internal sources and includes motivation from extrinsic sources for individuals who identify with an activity’s value and how it aligns with their sense of self. Controlled motivation is comprised of external regulation—a type of motivation where an individual acts out of the desire for external rewards or fear of punishment.

On the other hand, introjected regulation is motivation from “partially internalized activities and values” such as avoiding shame, seeking approval, and protecting the ego.

When an individual is driven by autonomous motivation, they may feel self-directed and autonomous; when the individual is driven by controlled motivation, they may feel pressure to behave in a certain way, and thus, experience little to no autonomy (Ryan & Deci, 2008).

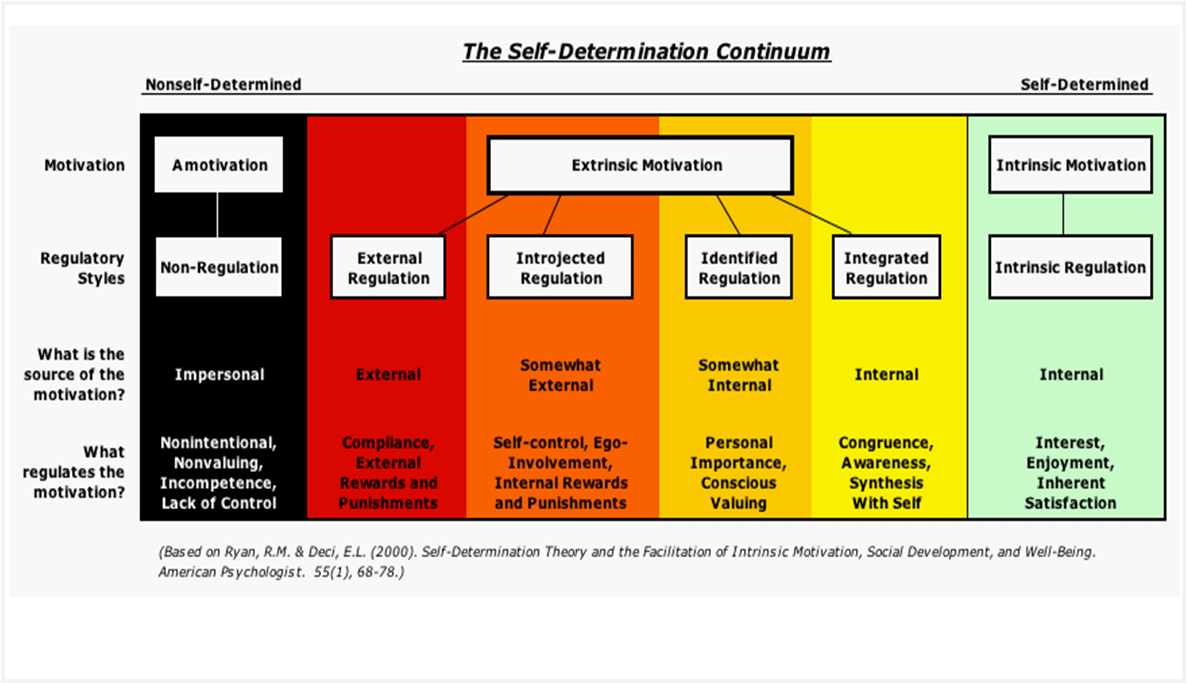

We are complex beings who are rarely driven by only one type of motivation. Different goals, desires, and ideas inform us what we want and need. Thus, it is useful to think of motivation on a continuum ranging from “non-self-determined to self-determined.”

At the left end of the spectrum, we have amotivation, in which an individual is completely non-autonomous, has no drive to speak of, and is struggling to have any of their needs met. In the middle, we have several levels of extrinsic motivation.

One step to the right of amotivation is external regulation, in which motivation is exclusively external and regulated by compliance, conformity, and external rewards and punishments.

The next level of extrinsic motivation is termed introjected regulation, in which the motivation is somewhat external and is driven by self-control, efforts to protect the ego, and internal rewards and punishments.

In identified regulation, the motivation is somewhat internal and based on conscious values and that which is personally important to the individual.

The final step of extrinsic motivation is integrated regulation, in which intrinsic sources and the desire to be self-aware are guiding an individual’s behavior.

The right end of the continuum shows an individual entirely motivated by intrinsic sources. In intrinsic regulation, the individual is self-motivated and self-determined, and driven by interest, enjoyment, and the satisfaction inherent in the behavior or activity he or she is engaging in.

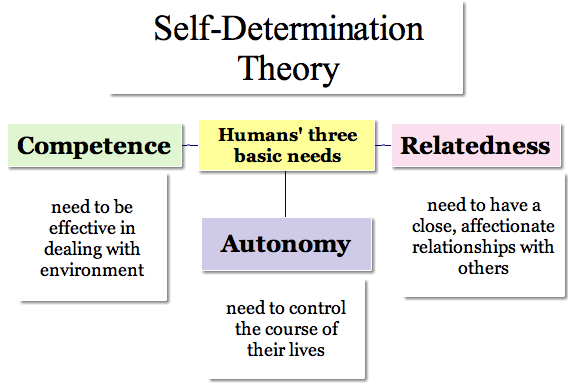

Although self-determination is generally the goal for individuals, we can’t help but be motivated by external sources—and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation are highly influential determinants of our behavior, and both drive us to meet the three basic needs identified by the SDT model:

According to the developers of SDT, Deci and Richard M. Ryan, individual differences in personality result from the varying degrees to which each need has been satisfied—or thwarted (2008). The two main aspects on which individuals differ include causality orientations and aspirations or life goals.

Causality orientations refer to how people adapt and orient themselves to their environment and their degree of self-determination in general, across many different contexts. The three causality orientations are:

Aspirations or life goals are what people use to guide their own behavior. They generally fall into one of the two categories of motivation mentioned earlier: intrinsic or extrinsic. Deci and Ryan provide affiliation, generativity, and personal development as examples of intrinsic life goals, while they list wealth, fame, and attractiveness as examples of extrinsic life goals (2008).

Aspirations and life goals drive us, but they are considered learned desires instead of basic needs like autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

SDT presents two sub-theories for a more nuanced understanding of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. These sub-theories are Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET) and Organismic Integration Theory (OIT) which help explain intrinsic motivation with regards to its social factors and the various degrees of contextual factors that influence extrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

Let’s take a deeper look:

According to CET intrinsic motivation can be facilitating or undermining, depending on the social and environmental factors in play. Referring to the Needs Theory, Deci & Ryan (1985,2000) argue that interpersonal events, rewards, communication and feedback that gear towards feelings of competence when performing an activity will enhance intrinsic motivation for that particular activity.

However, this level of intrinsic motivation is not attained if the individual doesn’t feel that the performance itself is self-determined or that they had the autonomous choice to perform this activity.

So, for a high level of intrinsic motivation two psychological needs have to be fulfilled:

Thus for CET theory to hold true, motivation needs to be intrinsic and have an appeal to the individual. It also implies that intrinsic motivation will be enhanced or undermined depending on whether the needs for autonomy and competence are supported or thwarted respectively.

It is believed that the use of the needs for autonomy and competence are linked to our motivations. Deci conducted a study on the effects of extrinsic rewards on people’s intrinsic motivation.

Results showed that when people received extrinsic rewards (e.g., money) for doing something, eventually they were less interested and less likely to do it later, compared to people who did the same activity without receiving the reward.

The results were interpreted as the participants’ behavior, which was initially intrinsically motivated, became controlled by the rewards which lead to an undermined sense of autonomy. This concept is beautifully explained in this video by RSA Animate.